|

|

Harveyís

Himalayan

Journal:

1995

14 September

Leave

Cumbria

, dropping off the cats at the cattery, and arrive at

Chichester

about 5.00. Sue has been ill

with diarrhoea for two days, not a good start to what we expect will be an

arduous trip. Meet up with Ben

for dinner at The Old Cross, and retire early to our tiny little attic

room at The Ship.

15 September

Woken at 6.00am by the sound of running water.

The roof is leaking, fortunately not onto our travel clothes.

We realise from the stains on the wall that it is not the first

time this roof has leaked, and I complain.

We get an apology, but nothing further, and the receptionist

doesnít seem surprised. Itís

still raining hard, so no leisurely shopping in

Chichester

. In the end we decide to

visit Petworth House, but itís closed.

We drive through

Sussex

in the rain. At the airport we

meet our guide,

Lorraine

. There will be about sixteen

in our party.

16 September

Itís a long flight but we have some legroom, enjoy the Royal Nepal

Airways food, and we both sleep. We

land in

Kathmandu

at dusk, so the views are disappointing. We

have a snack at the Base Camp and go straight to bed.

And straight to sleep.

17 September

We discover that our hotel, The Himalaya, is actually in Patan, but our

first bus tour is Kathmandu and off we go to the ancient

temple

of

Swayambunath

, perched on a slight hill. Itís

a strange mixture of Buddhism and Hinduism, and the place is seething with

vendors, monkeys, sleeping dogs ~ and even a few monks.

The

stupa is built over Ďthe light of Swambhuí (the self-born), protecting

it until the day when it can once again be allowed to shine on the world.

There is a man dressed in mourning clothes, all in white, making

offerings for a parent who has just died.

In the

temple

Tibetan

monks are sitting in rows, reading from books, some of them (mainly young

boys) chanting the prayers.

We discover that our hotel, The Himalaya, is actually in Patan, but our

first bus tour is Kathmandu and off we go to the ancient

temple

of

Swayambunath

, perched on a slight hill. Itís

a strange mixture of Buddhism and Hinduism, and the place is seething with

vendors, monkeys, sleeping dogs ~ and even a few monks.

The

stupa is built over Ďthe light of Swambhuí (the self-born), protecting

it until the day when it can once again be allowed to shine on the world.

There is a man dressed in mourning clothes, all in white, making

offerings for a parent who has just died.

In the

temple

Tibetan

monks are sitting in rows, reading from books, some of them (mainly young

boys) chanting the prayers.

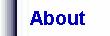

Then down to the old part of Khatmandu, to

Durbar Square

, where it is dirty and smelly. There

are some beggars, but it doesnít strike us as desperately poor.

Take lots of photos, mainly of street scenes and elaborately-carved

buildings. Would love to take

close-ups of some of the people but havenít the nerve.

There are some wonderful characters about, with holy men in rags

or splendid robes, imposing faces and long beards; women in colourful

saris, many of them arrestingly beautiful; children, some in rags, all looking

bright-eyed. The crowds

are good-humoured and we donít feel threatened, but we have been warned

against pickpockets.

We go to the home of Kumari, the Living Goddess.

There are lots of tourists in the courtyard, and in response to a

shout from one of the guides Kumari appears at one of the open windows.

She allows us to gawp at her for about 5 seconds and withdraws.

She is chosen at the age of 2 or 3 with the aid of astrologers, and

undergoes tests to prove that she is indeed a goddess.

She must be physically perfect, of course, have never shed blood,

and must remain serene when faced with horrifying images.

When we see her she is perhaps eight or nine years old, with heavy

eye make-up and dressed in red and gold.

She only leaves her home two or three times a year to attend

ceremonies. She has a private

tutor (and Michael Jackson videos!) but in the old days Kumari didnít

receive an education. When she

has her first period she will lose her divine status and another little

girl will take her place. An

ex-Kumari must find it difficult to adjust to ordinary life, although she

can marry. At one time it was

thought that a man who married such a girl would die within six months,

and the women had lonely unhappy lives.

Sue seems to be over her diarrhoea but she feels worn out and sleeps in

the afternoon. I walk back to

the bridge over the Bagmati river, the border between Patan and Khatmandu.

There are road works everywhere, and the cocktail of dust and

exhaust fumes is awful. Lots

of people are wearing masks, or holding scarves or hands over nose and

mouth. I come back to the

hotel for a swim and then dry off in the sun, looking across

Kathmandu

to the hills. There is a

rainbow, and then itís raining and I go back to the room.

We have an excellent meal in The Chalet and both feel a bit more

human.

18 September

Sue doesnít join me, but Iím up at 5.45am to take a sight-seeing

flight to Everest. The weather

forecast is not good, but we take off anyway.

Not for long. We hear

that Everest is covered with cloud, and after 15 minutes the flight is

aborted. We come back to the

hotel for breakfast, with a promise that we can try again tomorrow at no

extra charge..

There used to be three major cities in this part of

Nepal

:

Kathmandu

, Patan and Bhaktapur, each with its own

Durbar Square

. Now the cities have run into

each other, forming a vast, sprawling conurbation.

This morning, in the rain, we take a tour of Patan, although it

also seems to be called Lalitpur. We

visit the

Golden

Temple

, dedicated to the god of business. This

seems strange to our western eyes, used to clear divisions between

religion and commerce.

In the afternoon we go to a Tibetan refugee camp, and shed our first tears

of the trip. Probably not the

last. All the workers are

sitting on mats on the floor, and they flash us smiles as we walk through.

We buy two prayer mats at US$29 each and learn our first Tibetan

phrase, Tashi Delek (hello, goodbye, best wishes).

We drive through the suburbs, with modern housing and satellite dishes.

A house with two or three bedrooms costs £200/£300 per month.

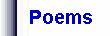

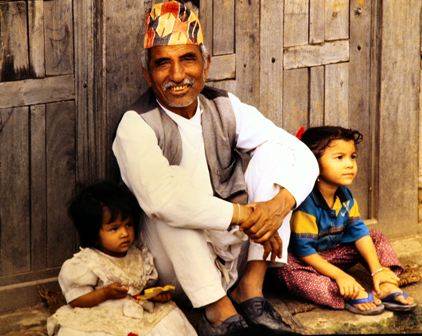

We are taken to three country villages, Pharping, Daksinkali and

Chapagaon. The bus stops at

the last one so that we can walk up the main street.

The entire village seems to have turned out for the occasion, and

the children follow us, giggling at the strange sight we must present.

We are equally taken with strange sights; water buffalo being

washed in a pond, old-fashioned corn stooks, and corn cobs hanging out to

dry like alien trees. Also some more familiar

sights: boys playing table tennis, girls skipping.

The whole place feels primitive, from way back in time, but there

is more laughter than we would hear in an English village.

We drive through the suburbs, with modern housing and satellite dishes.

A house with two or three bedrooms costs £200/£300 per month.

We are taken to three country villages, Pharping, Daksinkali and

Chapagaon. The bus stops at

the last one so that we can walk up the main street.

The entire village seems to have turned out for the occasion, and

the children follow us, giggling at the strange sight we must present.

We are equally taken with strange sights; water buffalo being

washed in a pond, old-fashioned corn stooks, and corn cobs hanging out to

dry like alien trees. Also some more familiar

sights: boys playing table tennis, girls skipping.

The whole place feels primitive, from way back in time, but there

is more laughter than we would hear in an English village.

Dinner again at The Chalet, which we enjoy again, but back at the room I

start with diarrhoea. I have

an awful night.

19 September

Feeling really grim, I get up at 5.45 again but I only make it to the

hotel lobby, then rush back to the room to throw up ~ again and again and

again. The flight to Everest

is cancelled again, but I know nothing about this.

By the time we are due to meet the rest of the party in the lobby

to catch the

Lhasa

flight I canít leave the bathroom. Sue

rushes up and down, from lobby to bedroom, trying to work out what happens

now. Fortunately, the

Lhasa

flight is delayed, and I have more time to recover.

We leave a suitcase behind and armed with sick bags I make it to

the airport and survive the flight. Only

just. When the plane lands I

rush to the toilet again. I am

still in there when everyone else (except Sue) has left the plane.

She tries to argue with Chinese soldiers that I need to be left

alone for a few more minutes, but they are suspicious and bang on the

door. I stagger out and down

the steps. By now I am weak

and dehydrated, and we have just landed at 12,000 feet.

We queue for immigration, but I canít stand up and there are no

seats. I sprawl on the floor,

still retching. Sue tries to

request a wheelchair for me, but all she is offered is a baggage trolley.

She declines on my behalf, but when we get through Customs the

guide who meets us has a wheelchair in the bus.

Visiting

Tibet

is a kind of pilgrimage for me, but I didnít prepare for a pilgrimage;

no fasting, no meditating. But

my bodyís reaction to the food and/or pollution in

Kathmandu

did the work for me. Crawling

about on the concrete floor stripped me of my usual impediments ~ ego,

pride and arrogance ~ and I emerge very humbly from the airport weak as a

new-born babe.

We are on a vast plain surrounded by high mountains.

The air is crystal clear, and we canít tell whether the mountains

are near or far. Our guide,

Jetsun, greets each of us with a karta (white silk scarf) as we board the

bus.

It is the traditional Tibetan greeting, a symbol of honesty,

sincerity and loyalty. We

have never before been greeted this way and although we are expecting it, I

shed my first tears in

Tibet

. Someone asks Jetsun what the

Tibetan national flag looks like. ďI

saw one once,Ē she says . . . .

The Chinese have banned anything that might imply that

Tibet

is a separate country. We are

in

China

, in the Tibetan Autonomous Region. Tibet the country only exists in

the minds of the exiles and their supporters.

The journey to

Lhasa

is about one and half hours, and Iím sick again. We

follow a fast-flowing river, passing through villages with prayer flags

fluttering, always surrounded by mountains.

We stop for a photo shoot but I stay on the bus.

At the Holiday

Inn

Sue has to see to everything and I am put to bed.

Around 8.30 a very young-looking female Chinese doctor comes to see

me. She seems to think

it is nothing serious. My

temperature is 37.2 but my heart and blood pressure are OK. She

prescribes pills, although Sue tells her that I wonít be able to keep

them down. We have brought our

own needles for just such an occasion, but Iím given pills.

I canít keep anything in my stomach, not even water (which I now

desperately need). I use an

oxygen pillow and settle into a dull constant nausea.

Eventually I sleep.

20 September

I have stopped vomiting but Sue has started.

We have both had headaches in the night (altitude) and Sueís

turned into acute nausea. Neither

of us wants food but we manage water.

I start to come round and take a much-needed shower, but reading

gives me a headache I am

content to sit and Sue sleeps.

Lorraine

brings us cup-a-soup, which we manage to drink.

We are now drinking water and green tea, so our bodies have

something to work on. By late

afternoon we feel strong enough to walk round the hotel, but we need

frequent rests. We donít

need an excuse to sit and admire one view.

We can see the Potola, the palace of the Dalai Lama, perched

improbably on a hill rising from the middle of the valley floor.

There is a second hill close by, We

know without having to be told that this is Chak Pori, the Iron Mountain,

which once housed the medical monastery, but along with thousands of other

monasteries the Chinese destroyed it.

Now the top of

Iron

Mountain

is graced by communication masts. The

Chinese brought so-called liberation to a backward and feudal people, but

in so doing they destroyed the educational and medical infrastructure run

by the monks. We look at this

very familiar view that we have never seen before and canít believe we

are really here. The Potola

was built for a living god. It

couldnít have been built anywhere else on earth.

We donít have much to show for our first day in

Tibet

, but we feel incredibly moved and privileged to be sharing this

experience. We can see the Potola, the palace of the Dalai Lama, perched

improbably on a hill rising from the middle of the valley floor.

There is a second hill close by, We

know without having to be told that this is Chak Pori, the Iron Mountain,

which once housed the medical monastery, but along with thousands of other

monasteries the Chinese destroyed it.

Now the top of

Iron

Mountain

is graced by communication masts. The

Chinese brought so-called liberation to a backward and feudal people, but

in so doing they destroyed the educational and medical infrastructure run

by the monks. We look at this

very familiar view that we have never seen before and canít believe we

are really here. The Potola

was built for a living god. It

couldnít have been built anywhere else on earth.

We donít have much to show for our first day in

Tibet

, but we feel incredibly moved and privileged to be sharing this

experience.

We

manage a light dinner ~ real food ~ and go to bed.

Already itís hard to remember just how awful I felt only a few

hours ago. Sue is still shaky

and I still have a temperature and a headache.

With altitude sickness itís important to breathe deeply, to get

enough oxygen to the brain. I

am familiar with Buddhist breathing exercises, but as soon as I start to

drift my breathing becomes shallow again, the headache comes back, and I

wake up. I donít get much

sleep, even with the help of the oxygen pillow.

21 September

I use up the last of the oxygen and as soon as I am upright the headache

goes.

We manage some breakfast, and struggle to be ready for todayís trip.

We missed yesterdayís excursion, but we are not going to miss the

Potala. Not if we have to

crawl through its 1,000 rooms. Itís

only a few minutes drive and as the bus waits at the first gate street

vendors cluster round, trying to push their wares through the windows.

The bus takes us up a zigzag path round the back of the Potola, the

tradesmenís entrance presumably, reversing up some of the stretches to

avoid turning tight corners. It

takes us as far as possible up the first few hundred feet, but we still

have a lot of steps ahead of us.

Lorraine

makes sure that we all stop for frequent rests.

Down below we can see the city of

Lhasa

, on a plain that stretches to mountains in the distance.

We are so close to the Potola walls that we canít actually see

much of the building itself. Sue

and I walk slowly hand in hand up the steep paths and into the palace that

we know so well through the books of Lobsang Rampa.

Where would our lives have gone without him?

The rest is a blur. Rooms and

rooms and rooms, corridors and steps, more steps, more corridors.

The steps are more like ladders, and in Lobsangís days they were

greasy with spilt yak butter. Some

of the rooms are vast. There

are statues and murals and ancient books.

There is some electricity, and enormous tubs of yak

butter with lots of wicks, but still it is gloomy, and mostly deserted.

A palace that for centuries had housed thousands of monks is now a

museum. Finally we are

on the roof, looking out over the city and the plain as The Dalai Lama

used to do. And the empty hill top of

Chakpori.  A man is loading a

large burner with juniper twigs. Three

girls sit on top of the walls, repairing them, slapping concrete on with

wooden paddles while they sing. A

puja is taking place in one corner, with drums and trumpets and chanting

monks. Jetsun has an uncle who

is a monk here, and she takes us close, ignoring the Chinese soldier in

mufty who has followed us everywhere. A man is loading a

large burner with juniper twigs. Three

girls sit on top of the walls, repairing them, slapping concrete on with

wooden paddles while they sing. A

puja is taking place in one corner, with drums and trumpets and chanting

monks. Jetsun has an uncle who

is a monk here, and she takes us close, ignoring the Chinese soldier in

mufty who has followed us everywhere.

Our progress has been so slow that we are late leaving.

The rest of the tourists have all gone, and as we go back down

through the palace lights are put out as we leave each room, and doors

shut behind us. It is an eerie

feeling, and yet the whole experience is familiar.

I cannot tell whether I am recognising things from Lobsangís

books or from a previous life. If

it is just from the books he must have been a good writer.

It is only as we return to the bus that we can look back and

finally see the main faÁade of the Potola in all its glory.

In the afternoon we visit the Norbulingka, the Dalai Lamaís

Summer

Palace

. Every year the people of

Lhasa wore their thick winter clothes until the Dalai Lama made the short

journey to the Norbulingka, signifying that it was officially summer, and

the people could change their clothes.

The gardens are sadly neglected, but the building itself is not too

bad. We donít get to see the

lake. I pick up a leaf from a

Bodhi tree to take to the Head Lama at the Tibetan Monastery in

Cumbria

, unaware until much later that Gesha-la has broken links with the Dalai

Lama.

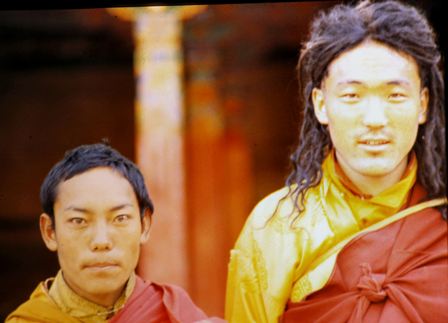

We see two monks, one with a shaved head, one with long hair.

The long-haired monk has just returned from a solitary retreat, and

needs help adjusting to the outer world again.

There is a guard dog on a roof.

We see a battered old kettle sitting on what looks like a satellite

dish. It comes to a boil with

the heat of the sun, reflected and focused by the metal dish.

Solar power, Tibetan-style. We

buy T-shirts emblazoned with the Tibetan characters of Om Mani Padme Hum.

Inside the palace there is a strange mixture of east and west.

There is a radiogram, a present from Nehru; a picture of kittens

from

London

. In one room a monk is

chanting and drumming, and we sit for a few minutes, but itís not

enough. It doesnít feel

alive. We walk through

the Dalai Lamaís private apartments and audience rooms, with a beautiful

gold & silver throne.

When a monk is Ďoff dutyí he might leave his spare robe on his prayer

mat, folded into a conical shape, awaiting his return.

The Dalai Lamaís robe sits on his throne, awaiting his return

from exile. There is an

enormous mural, showing the history of all the Dalai Lamas. The

mural is unfinished. The last

event depicted is the visit of the Fourteenth to

Beijing

in 1954. ďAnd thatís the

end of the story,Ē says Jetsun, almost apologetically.

ďPerhaps itís not the end,Ē I say to her, more in hope than

expectation.

It has been an amazing day. We

are light-headed from our sickness, light-headed from the altitude, and

the experience is almost hallucinatory.

It is not that we have fulfilled a life-long dream; when we read

Lobsang in our teens

Tibet

seemed as remote as the moon. They

used to say, see

Naples

and die. For

Naples

read

Lhasa

.

We both eat a good dinner. Sue

reckons this thin, dry air suits her.

Then we pack rucksacks ready for an early start in the morning.

We have left one suitcase in

Kathmandu

; we will leave our second at the Holiday Inn.

As with all good pilgrimages, we shed burdens along the way, and

tomorrow we will travel light. Again,

I donít sleep well.

22 September

We have an eight-hour drive ahead of us, but we set off late.

One of our party is suffering so much from altitude sickness that

Lorraine

has to arrange for her and her husband to fly back to

Kathmandu

. Itís 9.30 when we leave,

with a rucksack each and a few carrier bags.

We head west, back towards the airport, but soon turn off this road, over

a bridge, and say goodbye to tarmac. The

bus climbs up this rough, pot-holed road passing masses of wild flowers,

mostly blue and purple, to the

Kampala

Pass

at 5,000 metres. We stop for

photos, looking down at the villages by the river on the plateau below.

There are yaks, being watched by two girls.

The 12-year old is responsible for 7 animals; the younger girl has

4. Traditionally,

girls are sent out as yak-herders from the age of 6, and they are out from

dawn Ďtil dusk. They fire

stones from slings to keep the yaks under control.

The girls are too shy to show us, but our driver demonstrates.

Prayer-flags mark the highest point of the pass, and we are now looking

down the other side of the mountain at a sacred lake, Yamdok Yuntso.

It seems quite narrow, but stretches as far as we can see in either

direction, an amazing shade of blue, like the

Aegean

. There are mountains

everywhere, some snow-capped. The

bus takes us down to the lake and we drive along side it, stopping for a

picnic on the shingle beach. It

is our first taste of yak meat. Surprisingly,

it is tasty and tender. There

are vast herds of sheep and goats on the beach, although there doesnít

seem much for them to eat. The

herd boys, and other hangers-on, are keen to take our leftovers, so

perhaps that is why the animals are not enjoying green pasture higher up.

Prayer-flags mark the highest point of the pass, and we are now looking

down the other side of the mountain at a sacred lake, Yamdok Yuntso.

It seems quite narrow, but stretches as far as we can see in either

direction, an amazing shade of blue, like the

Aegean

. There are mountains

everywhere, some snow-capped. The

bus takes us down to the lake and we drive along side it, stopping for a

picnic on the shingle beach. It

is our first taste of yak meat. Surprisingly,

it is tasty and tender. There

are vast herds of sheep and goats on the beach, although there doesnít

seem much for them to eat. The

herd boys, and other hangers-on, are keen to take our leftovers, so

perhaps that is why the animals are not enjoying green pasture higher up.

The bus continues its bone-shaking drive by the lake for what seems like

hours, stopping only briefly for toilet breaks.

Gents to the left, ladies to the right, find your own boulder to

hide behind.

Lorraine

calls them pit stops, which Jetsun mis-hears.

She thinks we are stopping for pizza. We climb again to a high

pass. This is the

Karalla

Pass

, at over 5,000 metres. Jetsun

tells us that if we walk up a slight hill we will be able to see a tented

village, at the foot of a glacier. I

can walk up hills in Cumbria, but after a few yards my legs feel like

jelly, I canít breathe, I have a splitting headache, but I get to see

the nomad tents and the glacier. The

nomads rush over to us (no altitude sickness for them) and follow us back

to the bus. The children want

food, and we hand out more leftovers.

Jetsun tells us they would like anything we have left and gives

them our rubbish bag with cardboard containers, bits of string, apple

cores, empty water bottles, half-eaten sandwiches.

The children fight over it.

Nothing is wasted here. The

mothers ask for money.

We drive down the other side of the pass, and the bad road gets even

worse. Every few hundred

yards the surface has been washed away, and sometimes we canít imagine

how the bus will make it. On

one occasion a bulldozer is working on a landslide and has to clear a way

for us. The constant jolting

and thin air make for unpleasant travelling.

My headache persists for several hours.

One couple is quite ill but refuse oxygen.

We leave the road and drive through a quarry, a site for a

hydro-electric station. We

donít know whether it is a short-cut or a long diversion.

Eventually, at 7.00pm, we arrive in Gyantse, weary and exhausted.

Our hotel, the Gyantse Hotel, seems grim and Spartan, more like a

barracks. We sit down for a

buffet meal as a party. I

donít eat much. Our room is

very cold but we have snug quilts. Our

bodies still feel o be vibrating. It

has been a dreadful, unbelievable, unmissable day. Sue

sleeps for almost 10 hours.

We drive down the other side of the pass, and the bad road gets even

worse. Every few hundred

yards the surface has been washed away, and sometimes we canít imagine

how the bus will make it. On

one occasion a bulldozer is working on a landslide and has to clear a way

for us. The constant jolting

and thin air make for unpleasant travelling.

My headache persists for several hours.

One couple is quite ill but refuse oxygen.

We leave the road and drive through a quarry, a site for a

hydro-electric station. We

donít know whether it is a short-cut or a long diversion.

Eventually, at 7.00pm, we arrive in Gyantse, weary and exhausted.

Our hotel, the Gyantse Hotel, seems grim and Spartan, more like a

barracks. We sit down for a

buffet meal as a party. I

donít eat much. Our room is

very cold but we have snug quilts. Our

bodies still feel o be vibrating. It

has been a dreadful, unbelievable, unmissable day. Sue

sleeps for almost 10 hours.

23 September

Breakfast not very appetising. I

have rice gruel. Then we visit

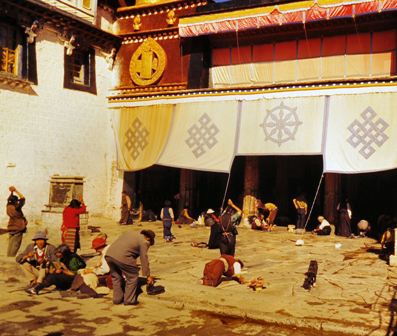

the Palchor Monastery. The

courtyard is full of dogs. The

monks are tolerant of them in case they have been monks in previous

incarnations. There are

statues of Buddha and other Bodhisatvas, and grainy copies of photos of

their spiritual leader. We

have been warned against handing out photos of The Dalai Lama; the Chinese

regard him as a splittist and have banned his photos, books and teachings.

This is a living monastery, not a museum, and the monks are

cheerful and joke with us. There

is an octagonal building with a golden dome known as Bakhor Chorten, the

chorten of 100,000 Buddhas. Outside

are huge brass prayer wheels. Inside

are five floors, each with side chapels and rows and rows of Buddha

statues.

Breakfast not very appetising. I

have rice gruel. Then we visit

the Palchor Monastery. The

courtyard is full of dogs. The

monks are tolerant of them in case they have been monks in previous

incarnations. There are

statues of Buddha and other Bodhisatvas, and grainy copies of photos of

their spiritual leader. We

have been warned against handing out photos of The Dalai Lama; the Chinese

regard him as a splittist and have banned his photos, books and teachings.

This is a living monastery, not a museum, and the monks are

cheerful and joke with us. There

is an octagonal building with a golden dome known as Bakhor Chorten, the

chorten of 100,000 Buddhas. Outside

are huge brass prayer wheels. Inside

are five floors, each with side chapels and rows and rows of Buddha

statues.

We are given the chance to walk up to the fortress on Dzong Hill.

Sue canít face the climb and stays to wander the streets of

Gyantse. I plod slowly up,

stopping on the way to photograph the view some nuns sitting in the

foreground. They are wise to

me, and want me to pose them while one of them borrows my camera.

The fortress is famous for an incident in 1903 that as an

Englishman abroad makes me feel uncomfortable.

The British Government thought that Tibet provided a channel

through which China and Russia could attack India and sent an expedition

led by Francis Younghusband to negotiate with the Dalai Lama for a British

legation in Lhasa. Younghusband

was accompanied by over 1,000 armed soldiers.

Not surprisingly, the Tibetans thought they were being invaded and

resisted. Gyantse had a

fortress with artillery, and the British laid siege..

When it became obvious that the Tibetan soldiers could not

withstand the siege many of them threw themselves off the battlements to

their death rather than surrender. Ironically,

on his retreat from

Tibet

, Younghusband had a mystical experience that suffused him with love for

the world and convinced him that man is divine.

He went on to found the World Congress of Faiths. the

foreground. They are wise to

me, and want me to pose them while one of them borrows my camera.

The fortress is famous for an incident in 1903 that as an

Englishman abroad makes me feel uncomfortable.

The British Government thought that Tibet provided a channel

through which China and Russia could attack India and sent an expedition

led by Francis Younghusband to negotiate with the Dalai Lama for a British

legation in Lhasa. Younghusband

was accompanied by over 1,000 armed soldiers.

Not surprisingly, the Tibetans thought they were being invaded and

resisted. Gyantse had a

fortress with artillery, and the British laid siege..

When it became obvious that the Tibetan soldiers could not

withstand the siege many of them threw themselves off the battlements to

their death rather than surrender. Ironically,

on his retreat from

Tibet

, Younghusband had a mystical experience that suffused him with love for

the world and convinced him that man is divine.

He went on to found the World Congress of Faiths.

We have lunch back at the hotel and then set off for Shigatse, a two hour

journey which takes three. No

mountain passes this time, we pass fields of ripened corn, and haymaking. We

ask Jetsun about village life and she makes an unscheduled stop to show

us. Sue feels this is

intrusive and doesnít go, but the photographers in the party canít

resist the opportunity. We are

taken to the house of the village headman.

The courtyard walls are covered in pats of yak dung, slapped on to

dry out. The residents do not

seem at all put out by this sudden visit, and we are given an impromptu

tour.

We have lunch back at the hotel and then set off for Shigatse, a two hour

journey which takes three. No

mountain passes this time, we pass fields of ripened corn, and haymaking. We

ask Jetsun about village life and she makes an unscheduled stop to show

us. Sue feels this is

intrusive and doesnít go, but the photographers in the party canít

resist the opportunity. We are

taken to the house of the village headman.

The courtyard walls are covered in pats of yak dung, slapped on to

dry out. The residents do not

seem at all put out by this sudden visit, and we are given an impromptu

tour.

We arrive in Shigatse in time for a short walk round the market before

dinner. The traders are quite

aggressive, clutching and pulling, and some members of the party are

unhappy. Sue doesnít like

the atmosphere. I buy

two carved figures, a man and a woman.

The trader assures me they are carved from yak bone, but it looks

more like plastic. Unwisely, I

reckon that out here yak bone is probably easier to get than plastic, and

it is only later that I see a ridge running down the side of the carvings,

left by the mould. I donít

mind. I feel I am putting some

tourist money into a Tibetanís hands rather than into

Beijing

ís coffers. After dinner we

take another walk, just to look at the light on the mountains.

24 September

Sue has a bad night with diarrhoea and nausea, and has difficulty

breathing. She takes

homeopathic remedies and I get her some oxygen.

She doesnít feel like breakfast (I have rice gruel again) but she

has recovered sufficiently to visit Tashilunpo Monastery.

This is the home of the Panchen Lama, the second highest after the

Dalai Lama, but he also is not in

Tibet

. After the last Panchen Lama

died his next incarnation was recognised and confirmed by the Dalai Lama

in exile. The young boy was

brought to Tashilunpo for training, but Beijing  feared a potentially

strong bond between the two high lamas that would attract a following both

within Tibet and in the wider world. They

denounced the boy as an imposter and took him to

Beijing

. He has not been seen since.

The regime in

Beijing

then Ďdiscoveredí the real Panchen Lama and took him under their wing.

A strange move for a communist regime that doesnít believe in

reincarnation, Buddhism, or religion of any kind.

The Chinese nominee had recently visited Shigatse and there had

been trouble, and we had fully expected that we would not be allowed in,

but things had quietened down again. feared a potentially

strong bond between the two high lamas that would attract a following both

within Tibet and in the wider world. They

denounced the boy as an imposter and took him to

Beijing

. He has not been seen since.

The regime in

Beijing

then Ďdiscoveredí the real Panchen Lama and took him under their wing.

A strange move for a communist regime that doesnít believe in

reincarnation, Buddhism, or religion of any kind.

The Chinese nominee had recently visited Shigatse and there had

been trouble, and we had fully expected that we would not be allowed in,

but things had quietened down again.

We are late leaving the hotel. We

assemble in the lobby and hand over our keys but we are kept waiting until

hotel staff check the rooms to make sure that we havenít damaged

anything or smuggled a towel in our rucksacks.

Tashilunpo is worth the wait, a huge monastery more like a village,

built for 5,000 monks. There

are crowds of people, and even though there are only 800 monks now, the

place feels really alive. We

walk across a huge courtyard where the Chinese-selected Panchen Lama

recently addressed the monks and into an assembly room which seats 2,000

monks, the floor crowded with snaking lines of empty cushions.

It is dark and vast, paintings adorning ceiling and walls, it feels

medieval. There is a tomb

stupa for each of the previous Panchen Lamas, and a 26.5 metre statue of

the Maitreya Buddha, the future incarnation, built by the ninth Panchen

Lama. In an inner courtyard what appears to be a jumble sale is

attracting attention.

Then we leave Shigatse for the drive back to

Lhasa

, following the Nyang Chu river. We

travel across plains, mostly cultivated, and through wild gorges and

deserts. The road surface is mostly good.

We see a yak-skin coracle making a river crossing, similar to the

one the Dalai Lama used during his escape.

We stop for another picnic, and again there are people waiting for

our leftovers. It takes six

hours to get back to the Holiday Inn.

Sue and I have had quite enough of the rest of the party, and we

have dinner by ourselves in the Hard Yak Cafť.

Then we leave Shigatse for the drive back to

Lhasa

, following the Nyang Chu river. We

travel across plains, mostly cultivated, and through wild gorges and

deserts. The road surface is mostly good.

We see a yak-skin coracle making a river crossing, similar to the

one the Dalai Lama used during his escape.

We stop for another picnic, and again there are people waiting for

our leftovers. It takes six

hours to get back to the Holiday Inn.

Sue and I have had quite enough of the rest of the party, and we

have dinner by ourselves in the Hard Yak Cafť.

25 September

Our 28th wedding anniversary.

Who would have thought it? We

celebrate by joining

Lorraine

, Jetsun and the party on a visit to Drepung Monastery, although Sue has

had another poor night. This

is a large sprawling village of a monastery.

I think Lobsang said its nickname was the rice bowl, because it

looked like a heap of rice spilled onto the mountainside.

This was also destroyed by the Chinese

but belatedly they realised the tourist value of colourful

monasteries and this is in the process of being repaired.

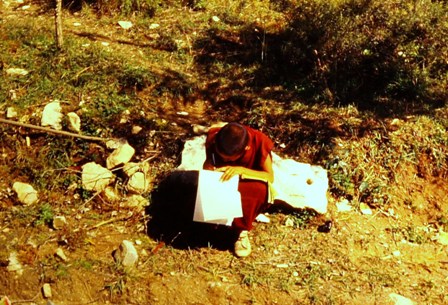

We

notice a small monk sitting by the roadside. He looks as though he

is doing a bit of last-minute homework. In the courtyard, a traditional debate is taking place between young monks.

Part of a monkís education is to learn his subject so well that

he can debate it from either side, and as each monk makes his point he

smacks his hands together. The

exertion is too much for Sue and she goes back to the bus, but I carry on

with the rest of the party through an enormous assembly hall. We

notice a small monk sitting by the roadside. He looks as though he

is doing a bit of last-minute homework. In the courtyard, a traditional debate is taking place between young monks.

Part of a monkís education is to learn his subject so well that

he can debate it from either side, and as each monk makes his point he

smacks his hands together. The

exertion is too much for Sue and she goes back to the bus, but I carry on

with the rest of the party through an enormous assembly hall.

We stop off at a carpet factory on the way back to

Lhasa

. In the bus, Jetsun tells us

some of her experiences. She

is unwilling to talk in public because tour guides are under constant

scrutiny, but on the bus she is safe.

She was sent to

China

for her education, and when she arrived she was teased for being an

unwashed backward Tibetan. When

she returned to

Tibet

she felt she did not know her own country.

She can hardly believe that some of us have seen The Dalai Lama.

We have lunch in our room and then go to the market, where Sue buys 7

scarves and 2 bowls. We leave

the party to do our own thing, we missed the Jokang on the first day and

want to se it before we leave.  This

is the peopleís monastery, very ancient, the destination of countless

pilgrimages. Some pilgrims do

the last stretch with prostrations. They

lie down, full length, in the dust, stand up, take one step forward, and

repeat the process over and over, hour after hour, sometimes day after

day. Tibetans believe that the

balance between good and evil is only maintained by keeping evil in check.

They see the landscape as a

manifestation of these forces, and the goddess of evil is controlled by

building religious edifices on her strategic body parts, such as her

wrists and ankles. The Jokang

is built on the heart of the goddess. This

is the peopleís monastery, very ancient, the destination of countless

pilgrimages. Some pilgrims do

the last stretch with prostrations. They

lie down, full length, in the dust, stand up, take one step forward, and

repeat the process over and over, hour after hour, sometimes day after

day. Tibetans believe that the

balance between good and evil is only maintained by keeping evil in check.

They see the landscape as a

manifestation of these forces, and the goddess of evil is controlled by

building religious edifices on her strategic body parts, such as her

wrists and ankles. The Jokang

is built on the heart of the goddess.

Inside, the Jokang is almost deserted, and we just glimpse the occasional

monk or pilgrim. Itís our

anniversary and we have the place to ourselves. There are the usual prayer

wheels, religious images and statues, candles, losing their novelty factor

but this place feels very spiritual, very special.

Outside, a storm hits

Lhasa

, and we wander through the dingy rooms with thunder crashing and echoing

all around us. Itís very

eerie.  We are not sure where

to go, what we are allowed to do, but eventually we emerge onto the roof

just as the rain stops, with spectacular views of The Potola.

We have to make our own way back to the hotel so we take a rickshaw

ride, costing 20 yuan for 25-minutes.

We stop twice to take photos, and when we get back to the hotel we

ask the driver to take our photo sitting in his rickshaw.

He is delighted, and shares the joke with some of the other drivers

waiting for fares. We are not sure where

to go, what we are allowed to do, but eventually we emerge onto the roof

just as the rain stops, with spectacular views of The Potola.

We have to make our own way back to the hotel so we take a rickshaw

ride, costing 20 yuan for 25-minutes.

We stop twice to take photos, and when we get back to the hotel we

ask the driver to take our photo sitting in his rickshaw.

He is delighted, and shares the joke with some of the other drivers

waiting for fares.

The party is taken to a traditional Tibetan house for dinner, although I

guess this is larger than most Tibetan houses.

This is the real thing, with yak in every course, and although

itís all rather greasy we manage quite well.

I think of the Monty Python spam sketch.

We are offered buttered tea, but I am the only one who drinks it

with any enjoyment.

The experiences of the last few days are stacking up, leaving us almost

reeling, and no doubt we will be months assimilating them, but being on

our own today in the Jokang somehow felt like an affirmation of our

journey together, not just in Tibet but over 30 years, from our Yorkshire

back streets to the top of the world.

26 September

We are woken at 4.45am and leave the hotel at 6.00.

This feels like the end of the holiday.

We have had enough of communal meals and would be happy to go

straight home, but we are flying back to

Nepal

. Somehow, Sue has been

nominated to arrange a collection for Jetsun and the driver.

She makes the presentation with a suitable Buddhist quotation,

although itís probably wasted on most of our party.

We have been surprised at the lack of interest in Buddhism and in

Tibet itself. For most of the

party it was just another country to tick off.

One lady held her handkerchief to her nose whenever we went round a

monastery.

We are woken at 4.45am and leave the hotel at 6.00.

This feels like the end of the holiday.

We have had enough of communal meals and would be happy to go

straight home, but we are flying back to

Nepal

. Somehow, Sue has been

nominated to arrange a collection for Jetsun and the driver.

She makes the presentation with a suitable Buddhist quotation,

although itís probably wasted on most of our party.

We have been surprised at the lack of interest in Buddhism and in

Tibet itself. For most of the

party it was just another country to tick off.

One lady held her handkerchief to her nose whenever we went round a

monastery.

The airport is chaotic, and we queue for an hour before the desk opens for

check-in. Being British, we

are prepared to queue in an orderly fashion, but we get bustled and

jostled by travellers who are not quite so patient.

Lorraine

tries to physically restrain some of them, but she is no match for a

German group. In consequence,

we get the last seats to be allotted, near the back of the plane.

Behind us the plane is empty, and we spread out to take all the

window seats. As we fly past

Everest, with spectacular views, the Germans from up-front plead with us

for a chance to take photographs. The

pilot banks and makes the most of the fly-past for our benefit.

Itís just another mountain, but somehow this is another moving

experience, very humbling. Perhaps

we are just wide open after Tibet, but one of our party sums it up.

ďGod is very close.Ē Behind us the plane is empty, and we spread out to take all the

window seats. As we fly past

Everest, with spectacular views, the Germans from up-front plead with us

for a chance to take photographs. The

pilot banks and makes the most of the fly-past for our benefit.

Itís just another mountain, but somehow this is another moving

experience, very humbling. Perhaps

we are just wide open after Tibet, but one of our party sums it up.

ďGod is very close.Ē

Sue had toyed with the idea of going straight to the Himalaya Hotel just

for two days of peace, but we donít have what it takes to try to make it

happen. Instead, our suitcases

are sent to the hotel and we are taken to Dhulikhel, a mountain retreat.

But this is a tour, and we have more sights to see along the way.

After the thin and clean air of Tibet it is hot and humid.

We have scarcely left Kathmandu airport before we stop at

Pashupatinath. This is a

scared Hindu site on the Bagmati river.

It is a total assault on the senses, with vendors, children and

monkeys all vying for attention. On

the opposite bank there is a temple dedicated to Shiva, with a large

representation of his linga, but we are not allowed there.

Two funerals are taking place, the mourners wailing round the

corpses on their pyres. The

men handle the bodies, infinitely tender, and the women retreat before the

fire is lit, traditionally by the eldest son.

It takes between three and five hours for a body to burn, shorter

for a good person; longer for a bad person.

Then the ashes are swept into the river, where children are

playing, to be carried down river, eventually to reach the

Ganges

. We in the west use the words

Ďin the midst of life there is deathí but we prefer to look the other

way. Here life and death

are closely entwined, and it all seems perfectly natural.

Except for the white people with their cameras.

We have one more stop, at the Bhuddist stupa at Bodnath, with the large

eye of Buddha painted on it. Sue

and I make our circumnambulations, three times in a clockwise direction,

then look at the shops all around.

We arrive at the Dhulikel Mountain Resort Hotel at 1.15, a cluster of red

brick and thatch buildings on a steep hillside looking over green valleys

and ridges to the distant snow-clad summits of the Himalayas.

The Tibetan border is 50 miles away.

Can we see

Tibet

? Who knows.

A border is manís invention, a line on a map.

There is no difference between a mountain in

Tibet

and a mountain in

Nepal

. The hotel has terraced

gardens with ginger lilies and frangipani.

It is beautiful and peaceful. We

should have come straight here from the airport.

We have a huge European lunch, and then the party sets off on a communal

walk. Sue and I head in the

other direction. We are picked

up by several small children who want help with money for their school

books.

We sit on the terrace with cocktails and watch dusk creeping over the

valleys below. Finally, only

the snowy mountain summits are sunlit, and then they disappear.

We have to be sociable again before and through dinner, European

food again, and canít wait to go to bed.

We sit on the terrace with cocktails and watch dusk creeping over the

valleys below. Finally, only

the snowy mountain summits are sunlit, and then they disappear.

We have to be sociable again before and through dinner, European

food again, and canít wait to go to bed.

27 September

We both sleep well, but I wake early.

I am sitting on the terrace at 6.00am, with orange juice and

coffee, watching the sun rise through the swirling mists.

The Himalayas, those ĎFar Pavilionsí, appear momentarily and

then disappear again. I am

joined by more of the party, who have been up on the ridge for the

sunrise.

We have time for another walk after breakfast, with more small children,

and leave Dhulikel at 11.00 for Bhaktapur, the third of the ancient

triangle of capital cities with Kathmandu and Pathan.

The party is given a quick tour with a local guide, through the

street market, past the pottery where the pots are drying in the sun, past

women spreading grain out to ripen, and then we are

allowed to do our own thing.  Bhaktapur

is ancient; old, old buildings with incredibly intricate wood carvings.

We go inside one, upstairs, now a cafť, and gawp at the whole of

Nepal passing in front of us down below.

We walk and walk, and shop, and we are picked up by two small boys.

They take us up winding dark alleyways to see the famous

500-yearold Peacock Window, and although we donít encounter any more

tourists we do see local life. Everyone

is friendly. We are told why.

Back in the 1970ís Nepal was on the Hippy Trail, and an

infrastructure developed to keep tens of thousands of tourists happy.

Now tourist numbers are much reduced, and the traders value any

business that comes their way. We

buy a carved turquoise statue, a wooden stupa, a T-shirt, a red dress and

some jewelry. But what we

really want, and didnít find in Tibet, in a thanka with a medical tree.

We donít find it here, either. The boys arrange a taxi for us,

back to the Himalaya Hotel, and we tip them $1 each.

Back at the hotel we have a simple dinner, just the two of us, at

Base Camp. Bhaktapur

is ancient; old, old buildings with incredibly intricate wood carvings.

We go inside one, upstairs, now a cafť, and gawp at the whole of

Nepal passing in front of us down below.

We walk and walk, and shop, and we are picked up by two small boys.

They take us up winding dark alleyways to see the famous

500-yearold Peacock Window, and although we donít encounter any more

tourists we do see local life. Everyone

is friendly. We are told why.

Back in the 1970ís Nepal was on the Hippy Trail, and an

infrastructure developed to keep tens of thousands of tourists happy.

Now tourist numbers are much reduced, and the traders value any

business that comes their way. We

buy a carved turquoise statue, a wooden stupa, a T-shirt, a red dress and

some jewelry. But what we

really want, and didnít find in Tibet, in a thanka with a medical tree.

We donít find it here, either. The boys arrange a taxi for us,

back to the Himalaya Hotel, and we tip them $1 each.

Back at the hotel we have a simple dinner, just the two of us, at

Base Camp.

28 September

The twice-aborted Everest fly-by is called off for the third time, and we

all get our money back ~ even though I didnít even get up to try for

this one. This is our last day

and we have to check out of the hotel, although we donít fly home until

evening. We take a taxi to

Durbar Marg and look round some up-market shops, buying our final

souvenirs, then walk to Thamel, which seems much more touristy.

Lunch at Annapurna Hotel, then a taxi back to Bodnath.

We walk round the stupa again and it comes on to rain.

We take shelter in a shop and strike up a conversation with the

owner. He has just started in

business. He was born in

Darjeeling to Tibetan parents but is now a Nepali citizen.

He has never been to Tibet. Finally, it is time to head for

the airport.

Post Script

I use the word ĎChineseí rather loosely in this journal.

When I talk somewhat critically about

Chinese policy in Tibet I am, of course, referring to the political regime

in Beijing. When travelling in China itself I always found the people just

as friendly as in Tibet.

We had agonised long and hard over making this trip.

Were we playing into the hands of the Chinese, by Ďrewardingí

them for their invasion and occupation of Tibet?

We felt that by showing an interest in Tibetan culture and Buddhist

shrines and monuments we might in some small way be encouraging Beijing to

recognise the value of preservation rather than eradication.

Whilst condemning the brutal Chinese invasion of Tibet, we recognised that

Tibet was perhaps in need of liberating from its old feudal ways.

Fifty years on Beijing had certainly improved roads and some

infrastructure, but the villagers and nomads appeared still to be living

at subsistence level. And yet,

life in the countryside was not dissimilar to life in the countryside in

Guilin or Sczechwan. Beijing

was not singling out Tibet for special treatment; this was simply the

Chinese way.

Ironically, in attempting to wipe out Tibetís feudal ways and

superstitions Beijing had adopted a sledgehammer approach.

When they smashed Tibetan Buddhism the monasteries broke into a

thousand splinters which scattered all over the world.

Tibetan lamas fled over the Himalayas and founded new monasteries

in India, Europe and North America. Tibet

is dead but Tibetan culture is alive and well.

Is there a solution? I think

so. The West is unwilling to

bring pressure to bear on Beijing and so Beijing is unlikely to release

political control of Tibet. But

with encouragement from the international community Beijing could turn

Tibet (or the TAR) into a Spiritual National Park, a Chinese version of

National Heritage status. They

could allow the Dalai Lama to return as spiritual leader in return for the

Dalai Lamaís promise to relinquish all political ambitions.

Beijing could gain international acclaim for such an innovative

move whilst retaining control of Tibetís valuable mineral resources.

Tourists would flock to see this wonder of the world and to spend

their tourist dollars. And the

people of Tibet would have the protection of tomorrowís worldís super

power whilst retaining the freedom to practice Tibetan Buddhism.

I put forward this idea in an article for The Tibetan Journal in

Autumn 1999. But the people of

Tibet are still waiting.

|