Bigger-Picture

Bigger-Picture

Windows on the world

Pacific Journal New

Zealand

Harvey

ís Pacific Journal ~ 2007

6.

Rarotonga to

Auckland

,

New Zealand

Depart 10.15;

Arrive 13.35

Air New

Zealand

Flight NZ023. Flying time 4 hours.

Distance 3010 km

Monday 5 March

I have set the alarm for 7.00am and requested a wake-up call, but we are out of

bed before either. We leave the

hotel at 8.15 and the plane leaves on time.

We leave

Rarotonga

on the morning of the health inspection. Every

household is checked to weed out breeding grounds for dengue-carrying

mosquitoes. Empty coconut shells

lying around in the backyard collecting puddles of rainwater are not allowed.

We are given a snack, and we read. I

finish Morris Westís The Navigator,

a Polynesian journey into the Pacific and into the human condition.

Some experts believe that the Polynesian explorers couldnít navigate,

that they simply drifted until they happened upon an island.

Reading this novel I have no doubt that they could navigate.

We cross the international date line, and suddenly itís tomorrow.

Tuesday 6 March

It takes a while to clear customs in

Auckland

. I mention cricket to the

immigration officer (the world cup is just about to start in the

West Indies

) but he follows football and is a Tottenham fan.

We collect the car we hired back in the

UK

and off we go, roadmaps at the ready.

Mercure Hotel,

Customs Street

,

Auckland

,

New Zealand

Locataion: 36:53:00S 174.45.00E (GMT +13) NZ$2.80

= £1

The roads are wide and well signed, the suburbs are green and spacious, and we

donít notice any slums or shanties. The

shopping streets downtown look affluent. We

lose our way once, but weíre soon checking into the hotel, where we have

glimpses of the harbour from our room on the seventeenth floor.

We have a drink and then Sue is ready to sample the shops and I want to

look at the harbour. We do both, in

bright sunshine, and the waterfront reminds me of

Portsmouth

, albeit on a grander scale. Across

the water are lots of trees and what looks like more suburbs, but we canít

tell whether there are islands or this is the other side of the bay.

We go back to the hotel to get changed, and then choose a waterfront

restaurant at random. Earlier it had

been hot, but now we are sitting outdoors in the shade and the breeze feels

cold. We both enjoy the meal (I have

a fish called terrakihi) but we are glad to forego our dessert and leave our

windy table.

Wednesday 7 March

Sue has a disturbed night, but on the whole she is sleeping more hours than she has for years. Breakfast is on

the 12th floor, with splendid views over the city and harbour.

As we eat we watch the ferries coming and going, and the rain clouds

scudding across the bay. Sue makes a

waffle, and feels rather pleased with herself.

We check out at 9.30 and within a few minutes we pick up Highway 1

heading north over the harbour bridge. Again,

the suburbs are attractive, gradually giving way to green, undulating

countryside. In parts it is not

unlike

Britain

, except for the profusion of tree ferns. We

even see a herd of Belted Galloways, more cows together than we have ever seen

in Dumfries and

Galloway

. The rain is intermittent, but one

shower is torrential. We stop for

lunch at Whangarei. We drive round

the industrial areas for a while before we find the town centre, but when we do

itís very pleasant. I am struck by

the notices in several shops informing would-be truants that the police or the

truant officer will be called if students are loitering during school hours.

We donít know how effective the system might be, but it seems more

sensible than the latest approach adopted in the

UK

, whereby mothers of truants are threatened with imprisonment.

she has for years. Breakfast is on

the 12th floor, with splendid views over the city and harbour.

As we eat we watch the ferries coming and going, and the rain clouds

scudding across the bay. Sue makes a

waffle, and feels rather pleased with herself.

We check out at 9.30 and within a few minutes we pick up Highway 1

heading north over the harbour bridge. Again,

the suburbs are attractive, gradually giving way to green, undulating

countryside. In parts it is not

unlike

Britain

, except for the profusion of tree ferns. We

even see a herd of Belted Galloways, more cows together than we have ever seen

in Dumfries and

Galloway

. The rain is intermittent, but one

shower is torrential. We stop for

lunch at Whangarei. We drive round

the industrial areas for a while before we find the town centre, but when we do

itís very pleasant. I am struck by

the notices in several shops informing would-be truants that the police or the

truant officer will be called if students are loitering during school hours.

We donít know how effective the system might be, but it seems more

sensible than the latest approach adopted in the

UK

, whereby mothers of truants are threatened with imprisonment.

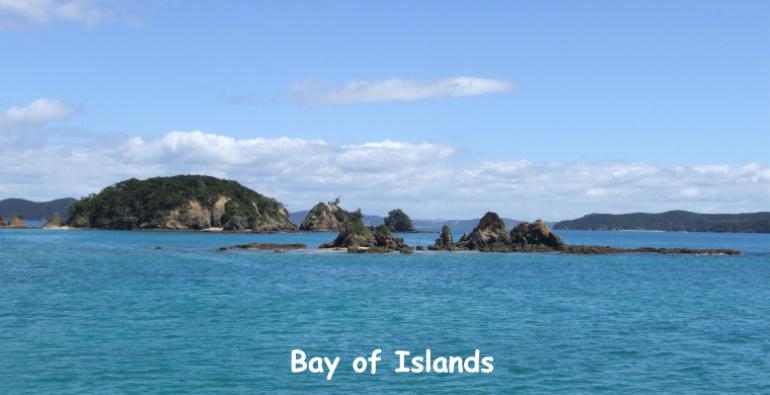

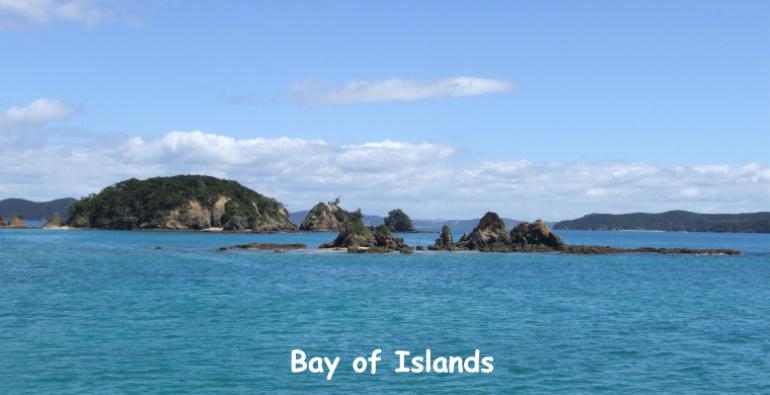

Duke of Marlborough Hotel, Russell,

Bay of Islands

,

New Zealand

We continue north. Knowing that we

donít have much further to go, I decide weíll take the

Old Russell Road

by the coast rather than queue for the car ferry at Opua.

Itís a bad choice. The road

is pretty, but narrow, twisting and up and down.

It is slow going and seems to take forever, and by now the sun is out and

itís hot. We alternate between the

heat and the aircon. Itís a long

time before we start to have glimpses of the sea, but when we do the views are

stunning: turquoise bays, sandy beaches, inlets, cliffs, islands; just our kind

of coastline. When we eventually

reach Russell it doesnít quite match some of the views we have passed, but it

is very attractive for all that. The

town itself is like a miniature version of

Camden

,

Maine

, and the hotel is a grand old building (well, this version was built in 1933

actually) with verandas on the edge of the harbour.

The original Duke of Marlborough, built in 1827, was granted the first

liquor licence issued in

New Zealand

when it became part of the

British Empire

in 1840: licence No. 1. Our

room is spacious, with a big window looking out on the harbour, but there is no

air conditioning and the ceiling fan is not up to the task of countering the

heat from the sun all afternoon. Sue

is whacked from the journey and sleeps, notwithstanding the heat.

I start my new book, Great Tales

from New Zealand History by Gordon McLauchlan.

It has over 40 short factual stories which I hope will help to clear up

my almost-total ignorance of NZ. When

Sue comes round we take a stroll along the waterfront, back through the town,

and have dinner at the hotel bistro on the veranda as the sun sets over the

Bay

of

Islands

. We are out of the wind here, and

even when the sun disappears the temperature is pleasant.

Thursday 8 March

Sue wants to check her emails and I want to explore, so after breakfast we book

a tour for the afternoon and go our separate ways.

I take the walk up

Sue wants to check her emails and I want to explore, so after breakfast we book

a tour for the afternoon and go our separate ways.

I take the walk up

Telegraph Hill, not far but quite steep. The

views are spectacular: back down to Russell and the harbour; on to the headland

of Tapeka; and out into the Bay. This

is where the Union Flag was raised following the signing of the Treaty of

Waitangi in 1840 but, disillusioned with the way things worked out, Hone Heke

(first chief to sign the treaty) cut down the flagstaff four times.

The British didnít see the warning signs and in 1845 found themselves

fighting the Maori in the

Battle

for Kororareka. Kororareka was the

old name for Russell, much more romantic until you discover that it means sweet

blue penguin (as in soup).

Back in Russell I bump into Sue (itís a small town) and we buy a snack for a

picnic lunch. I also buy an

Australian bush hat (my panama seems totally inappropriate here) and some ear

drops to try to clear up the deafness in my left ear that has persisted since

the flight from

Tahiti

.. Then we separate again, and I go

to see the church, the oldest in

New Zealand

, with bullet holes in the wooden walls from the

Battle

of 1845. The largest memorial in

the churchyard is to a Maori chief, Tamati Waka Nene, who worked for peace and

unity between the Maori and the Pakeha (the British) for over 30 years.

His portrait is inside the church. I

donít remember seeing any similar tribute to an Aborigine in

Australia

, and I start thinking that integration between residents and settlers in

New Zealand

must have been better than in most countries I have visited.

Sue has had a nap at the hotel, and at 1 oíclock we set off for a cruise round

the

Bay

of

Islands

. The boat is a large, fast

catamaran, and we move serenely out of

Russell

Harbour

in glorious sunshine, but the man providing the commentary warns of a Pacific

swell as we get further out. Sue and

I are tucking into our lunch as he gives instructions on what to do if we are

sea sick. No-one else is eating and

we wonder if we are pushing our luck. But

the scenery is stunning: islands, beaches, bays, hills, all bathed in sunshine,

the  overall effect as beautiful as we have seen anywhere in the world.

There are several large shoals of fish on the surface, some being farmed

by sea birds. We go right out to

Cape

Brett

, where there is a lighthouse, abandoned in the 1970ís.

When it was manned supplies were handed ashore in baskets (boats

couldnít land) and then winched up a steep railway by horse power: one horse

walking round and round a capstan. Near

the lighthouse is a small basalt island with an arch just large enough for a

boat to pass through. By now we are

in the gentle Pacific swell that we had been promised (although no-one is sick)

and as we approach the ĎHole in the Rockí I remember how difficult it was to

bring my motorboat into its Derwentwater boathouse when there was a lake swell

and an onshore breeze. In fact, when

we get into the arch there is clear water on either side, and the manoeuvre was

probably easier than my boathouse. We

pass right through the arch, and then as we watch the next boat coming through

we get a call from our sister boat: dolphins have been spotted.

They are about twenty minutes away, so off we go, the catamaran moving at

speed for the first time. Sure

enough, there are about a dozen dolphins, including one baby.

They swim alongside the boat, under the boat, jump and dive; all in all

they put on an amazing impromptu display, but most of our photographs are of

disappearing tails.

overall effect as beautiful as we have seen anywhere in the world.

There are several large shoals of fish on the surface, some being farmed

by sea birds. We go right out to

Cape

Brett

, where there is a lighthouse, abandoned in the 1970ís.

When it was manned supplies were handed ashore in baskets (boats

couldnít land) and then winched up a steep railway by horse power: one horse

walking round and round a capstan. Near

the lighthouse is a small basalt island with an arch just large enough for a

boat to pass through. By now we are

in the gentle Pacific swell that we had been promised (although no-one is sick)

and as we approach the ĎHole in the Rockí I remember how difficult it was to

bring my motorboat into its Derwentwater boathouse when there was a lake swell

and an onshore breeze. In fact, when

we get into the arch there is clear water on either side, and the manoeuvre was

probably easier than my boathouse. We

pass right through the arch, and then as we watch the next boat coming through

we get a call from our sister boat: dolphins have been spotted.

They are about twenty minutes away, so off we go, the catamaran moving at

speed for the first time. Sure

enough, there are about a dozen dolphins, including one baby.

They swim alongside the boat, under the boat, jump and dive; all in all

they put on an amazing impromptu display, but most of our photographs are of

disappearing tails.  This

is a camcorder activity, and we donít manage to capture one jump between us.

The crew are excited by the baby, and they tell us that there is a high

infant mortality rate for dolphins. They

need to maintain a body temperature similar to ours, but until they have

developed a protective layer of blubber they are vulnerable to hypothermia.

They need feeding constantly (up to twenty times an hour) and if one dies

it has been known for the mother to keep the dead baby with her for days,

balanced on her nose, refusing to abandon it until the body starts to decompose.

When there are babies, boats must not stay too long and no-one is allowed

to swim with them. We are

entertained and sobered.

This

is a camcorder activity, and we donít manage to capture one jump between us.

The crew are excited by the baby, and they tell us that there is a high

infant mortality rate for dolphins. They

need to maintain a body temperature similar to ours, but until they have

developed a protective layer of blubber they are vulnerable to hypothermia.

They need feeding constantly (up to twenty times an hour) and if one dies

it has been known for the mother to keep the dead baby with her for days,

balanced on her nose, refusing to abandon it until the body starts to decompose.

When there are babies, boats must not stay too long and no-one is allowed

to swim with them. We are

entertained and sobered.

Back at Russell we have a hot drink and then wander round town again.

We book our evening meal at

Kamakura

, on The Strand near Dukeís. I

have a (

New Zealand

) lamb rack and Sue has vegetarian. We

both enjoy it, but although itís expensive itís not very substantial and Sue

heads off to buy a bar of chocolate whilst I sit with my coffee.

Whilst we eat the sun falls behind cloud but eventually re-emerges just

above the horizon for a somewhat subdued sunset.

Friday 9 March

After breakfast I go to the internet cafť (actually a charity shop) to check

emails, and then we catch the ferry to Paihia.

There is more cloud about today and itís cooler, but still very

pleasant on the water. We look round

the tourist shops and have lunch at a restaurant on the waterís edge.

Sue sees two meals being sent back, and ours arenít exciting, and too

late we realise we are in the wrong place. We

enquire how to get to the Treaty Grounds and discover that itís a half-hour

walk each way. Sue doesnít fancy

that, but as we head for the taxi rank we notice a rather exotic looking vehicle

called the Paihia Tuk Tuk Shuttle Service, and we are taken over the river to

Waitangi for $4 each. We arrive just

in time for the 1.30 guided tour, which we share with two other English couples.

One of the Englishmen insists on asking questions which we feel are in

poor taste, but our guide displays all the dignity, grace and control that one

would expect from a Maori who can trace his ancestry back to the first canoe.

Some Europeans argue that

New Zealand

was settled by a fleet of canoes, but our guide insists that there never was a

ďgreat fleetĒ. He tells us that

over several centuries a number of canoes made the journey from the legendary

(or mythical?) Maori home on the

island

of

Hawaiki

. Each canoe (or waka)

was capable of holding up to 200 people, and we are shown one built in modern

times. In fact, our guideís

great-grandfather worked on it. 35

metres long, it consists of three giant Kauri trees, cut into planks and fit

together when the wood was still green, so that as the planks season and shrink

the waka becomes watertight without

the need for caulking. When the

third tree was cut it remained stubbornly standing until prayers were said,

whereupon it crashed to the ground and the jubilant workers launched into an

impromptu haka.

The waka is in a purpose-built whare

(house) near the beach where Captain William Hobson landed in 1840 with

instructions to make a treaty with the Maori, and we follow the path he took up

to the small house where James Busby lived as ďBritish ResidentĒ.

Busby had been chief representative of the British Government since 1833,

charged with maintaining peace but without any of the powers he would have had

as Governor. He acted mainly as

mediator, and in 1835 he hosted a gathering of northern chiefs who signed the

Declaration of the Independence of New Zealand.

The newly independent state could not maintain law and order, and so many

of the chiefs were prepared to relinquish freedom for the protection of the

British Empire

. We approach the house across a

large lawn, on which the draft treaty had been read to the hundreds of Maori and

scores of European. The document had

been drafted by Busby and Hobson and translated by Williams, the missionary,

none of them legal or constitutional experts.

The Maori debated it all day and into the night, and 43 chiefs signed an

amended version the following day. Our

guide believes that although flawed in detail the treaty still reads well as a

whole and resulted in the Maori and Pakeha

becaming one people.

Busbyís house is now known as the Treaty House, although the signing took

place where the flagstaff now stands. Nearby

stands the Whare Runanga, a ceremonial meeting house erected to mark the

centenary celebrations in 1940. It

is splendid. The whole of the

interior is carved and woven to represent the entire story of the Maori, just as

the carved tattoos on the face of a warrior tell his story.

Because it is not an actual meeting house we are allowed to take

photographs, but although it might not be the real thing we still find it an

emotional experience. We go back to

the visitorsí centre for some traditional dancing and singing, including the

haka made famous by the All Blacks. One

of the songs is familiar and beautiful. Billy

Connelly sang it when he came to the

Bay

of

Islands

on his World Tour of New Zealand.

Busbyís house is now known as the Treaty House, although the signing took

place where the flagstaff now stands. Nearby

stands the Whare Runanga, a ceremonial meeting house erected to mark the

centenary celebrations in 1940. It

is splendid. The whole of the

interior is carved and woven to represent the entire story of the Maori, just as

the carved tattoos on the face of a warrior tell his story.

Because it is not an actual meeting house we are allowed to take

photographs, but although it might not be the real thing we still find it an

emotional experience. We go back to

the visitorsí centre for some traditional dancing and singing, including the

haka made famous by the All Blacks. One

of the songs is familiar and beautiful. Billy

Connelly sang it when he came to the

Bay

of

Islands

on his World Tour of New Zealand.

We have a drink and then I go back to the Treaty House to look inside.

The House and Grounds were granted to the nation in 1932, in time for the

centenary celebrations to be organised, which some 10,000 people attended.

Although forgotten about and neglected for much of the previous 100

years, Waitangi is now regarded as the birthplace of

New Zealand

. We walk back into Paihia and take

the ferry over to Russell, the erstwhile lawless whaling town (Hell-hole of the

Pacific) that the treaty was designed to clean up.

It worked. Russell today is

as genteel as an English spa, spoilt only (for me) by the all-pervading smell of

cooking oil from the various cafťs and restaurants.

We eat at Dukes and go to our bedroom, situated over the kitchens, and

the oily cooking smells drift up and in through our open bathroom window.

Saturday 10 March

We had thought about driving up to 90

Mile

Beach

, although we know that rental cars are not allowed on the beach itself, but

Sue is wilting under the pressure and doesnít want to spend the day in the

car. She decides she will stay in

town and I take a walk up Flagstaff Hill and down the other side to Tapeka,

about three miles away near the end of the peninsula.

Itís a lovely little spot, with perhaps 100 houses with well-tended

gardens. Thereís a beach on one

side, with the calm waters of the bay, and rough water on the other side of the

isthmus, with waves breaking on the rocks. I

walk back up the hill and go back to Russell through Kororareka Point Scenic

Reserve. Itís a Kiwi Zone, which

means no dogs without leads. The

birds are declining in numbers as their natural habitat shrinks, and being

flightless they are particularly vulnerable to dogs.

No sign of Kiwis, or blue penguins. The

path winds through dense forest, with tree ferns much in evidence, and drops

down to

Watering

Bay

. At low tide you can walk into

Russell on the rocky beach, but not now, and I have to climb part way up the

hill again.

Back at the hotel I sit on the beach and wait for Sue, but instead I get a text

message: ďCome to the grass square ASAP.Ē

Mildly alarmed (has she had an accident?) I hurry over to find a small

festival taking place. I have missed the parade but I see Sue and we watch young children in traditional dress and

painted tattoos dancing and singing. We

are enchanted, and we have a snack there so we can go on watching the

performances. On the way back to the

hotel, but away from the main festival, we see another dance troupe in

traditional dress. They are all

white children, and several of the white mothers join in, swinging pom-poms,

perhaps familiar with the routines from their own childhood.

It dawns on us that the first set of dancers were mostly coloured.

Maori in one part of town, Pakeha

in another. Hmm.

Perhaps the ďOne People, One NationĒ concept doesnít quite filter

through to suburbia. Nevertheless,

it is good to see Maori traditions being embraced so whole-heartedly.

the parade but I see Sue and we watch young children in traditional dress and

painted tattoos dancing and singing. We

are enchanted, and we have a snack there so we can go on watching the

performances. On the way back to the

hotel, but away from the main festival, we see another dance troupe in

traditional dress. They are all

white children, and several of the white mothers join in, swinging pom-poms,

perhaps familiar with the routines from their own childhood.

It dawns on us that the first set of dancers were mostly coloured.

Maori in one part of town, Pakeha

in another. Hmm.

Perhaps the ďOne People, One NationĒ concept doesnít quite filter

through to suburbia. Nevertheless,

it is good to see Maori traditions being embraced so whole-heartedly.

Later in the afternoon I go to the amphitheatre by the visitorsí centre to

watch the Russell Theatre Group telling the story of the

Battle

for Kororareka in 1845, which took place following the breaking of the

flagstaff on Maiki Hill for the fourth time.

The actors, in costume, read eye-witness accounts of the day.

It doesnít reflect well on the Pakeha,

who withdrew to their ships and watched the victorious Maori burn the houses

(but not the church) from a safe distance. Order

was eventually restored but the Maori had made their point, and the British

became more circumspect in their dealings. There

are probably a score or so of actors, but only one is Maori.

We have fish & chips on the veranda in front of the hotel and drive over to

Tapeka in the evening sunlight. Then

itís back to the room to pack. Without

air-conditioning itís hot.

Sunday 11 March

We wake at 6.30, before the alarm, and after a quick breakfast weíre on the

road before 8.00. It took us a lot

longer to get to Russell, but we think it should take us three and a half hours

to get to

Auckland

. We need to check in by 12.30 so

we donít have much leeway for hold-ups. Itís

Sunday morning, and weíre not sure of the ferry timings at Opua, but a boat is

pulling in as we arrive at the terminal and we cross in few minutes.

Itís a good run all the way apart from a couple of heavy showers and we

arrive at the airport at 11.00. There

are the usual preliminaries: fill up the car with petrol, return the car, check

in, pay the departure tax, have a snack; and then we take off on time at 14.35.

Next

leg:

Next

leg:

7.

Auckland

to Brisbane

Back

to Itinerary

Bigger-Picture

Bigger-Picture Bigger-Picture

Bigger-Picture she has for years. Breakfast is on

the 12th floor, with splendid views over the city and harbour.

As we eat we watch the ferries coming and going, and the rain clouds

scudding across the bay. Sue makes a

waffle, and feels rather pleased with herself.

We check out at 9.30 and within a few minutes we pick up Highway 1

heading north over the harbour bridge. Again,

the suburbs are attractive, gradually giving way to green, undulating

countryside. In parts it is not

unlike

she has for years. Breakfast is on

the 12th floor, with splendid views over the city and harbour.

As we eat we watch the ferries coming and going, and the rain clouds

scudding across the bay. Sue makes a

waffle, and feels rather pleased with herself.

We check out at 9.30 and within a few minutes we pick up Highway 1

heading north over the harbour bridge. Again,

the suburbs are attractive, gradually giving way to green, undulating

countryside. In parts it is not

unlike  Sue wants to check her emails and I want to explore, so after breakfast we book

a tour for the afternoon and go our separate ways.

I take the walk up

Sue wants to check her emails and I want to explore, so after breakfast we book

a tour for the afternoon and go our separate ways.

I take the walk up  overall effect as beautiful as we have seen anywhere in the world.

There are several large shoals of fish on the surface, some being farmed

by sea birds. We go right out to

overall effect as beautiful as we have seen anywhere in the world.

There are several large shoals of fish on the surface, some being farmed

by sea birds. We go right out to  This

is a camcorder activity, and we donít manage to capture one jump between us.

The crew are excited by the baby, and they tell us that there is a high

infant mortality rate for dolphins. They

need to maintain a body temperature similar to ours, but until they have

developed a protective layer of blubber they are vulnerable to hypothermia.

They need feeding constantly (up to twenty times an hour) and if one dies

it has been known for the mother to keep the dead baby with her for days,

balanced on her nose, refusing to abandon it until the body starts to decompose.

When there are babies, boats must not stay too long and no-one is allowed

to swim with them. We are

entertained and sobered.

This

is a camcorder activity, and we donít manage to capture one jump between us.

The crew are excited by the baby, and they tell us that there is a high

infant mortality rate for dolphins. They

need to maintain a body temperature similar to ours, but until they have

developed a protective layer of blubber they are vulnerable to hypothermia.

They need feeding constantly (up to twenty times an hour) and if one dies

it has been known for the mother to keep the dead baby with her for days,

balanced on her nose, refusing to abandon it until the body starts to decompose.

When there are babies, boats must not stay too long and no-one is allowed

to swim with them. We are

entertained and sobered. Busbyís house is now known as the Treaty House, although the signing took

place where the flagstaff now stands. Nearby

stands the Whare Runanga, a ceremonial meeting house erected to mark the

centenary celebrations in 1940. It

is splendid. The whole of the

interior is carved and woven to represent the entire story of the Maori, just as

the carved tattoos on the face of a warrior tell his story.

Because it is not an actual meeting house we are allowed to take

photographs, but although it might not be the real thing we still find it an

emotional experience. We go back to

the visitorsí centre for some traditional dancing and singing, including the

haka made famous by the All Blacks. One

of the songs is familiar and beautiful. Billy

Connelly sang it when he came to the

Busbyís house is now known as the Treaty House, although the signing took

place where the flagstaff now stands. Nearby

stands the Whare Runanga, a ceremonial meeting house erected to mark the

centenary celebrations in 1940. It

is splendid. The whole of the

interior is carved and woven to represent the entire story of the Maori, just as

the carved tattoos on the face of a warrior tell his story.

Because it is not an actual meeting house we are allowed to take

photographs, but although it might not be the real thing we still find it an

emotional experience. We go back to

the visitorsí centre for some traditional dancing and singing, including the

haka made famous by the All Blacks. One

of the songs is familiar and beautiful. Billy

Connelly sang it when he came to the  the parade but I see Sue and we watch young children in traditional dress and

painted tattoos dancing and singing. We

are enchanted, and we have a snack there so we can go on watching the

performances. On the way back to the

hotel, but away from the main festival, we see another dance troupe in

traditional dress. They are all

white children, and several of the white mothers join in, swinging pom-poms,

perhaps familiar with the routines from their own childhood.

It dawns on us that the first set of dancers were mostly coloured.

Maori in one part of town, Pakeha

in another. Hmm.

Perhaps the ďOne People, One NationĒ concept doesnít quite filter

through to suburbia. Nevertheless,

it is good to see Maori traditions being embraced so whole-heartedly.

the parade but I see Sue and we watch young children in traditional dress and

painted tattoos dancing and singing. We

are enchanted, and we have a snack there so we can go on watching the

performances. On the way back to the

hotel, but away from the main festival, we see another dance troupe in

traditional dress. They are all

white children, and several of the white mothers join in, swinging pom-poms,

perhaps familiar with the routines from their own childhood.

It dawns on us that the first set of dancers were mostly coloured.

Maori in one part of town, Pakeha

in another. Hmm.

Perhaps the ďOne People, One NationĒ concept doesnít quite filter

through to suburbia. Nevertheless,

it is good to see Maori traditions being embraced so whole-heartedly.  Next

leg:

Next

leg: