Bigger-Picture

Bigger-Picture Bigger-Picture

Bigger-Picture

Windows on the world

Pacific Journal Easter Island

3.

LAN-Chile

Flight LA755. Flying time 5.25

hours. Distance 3,600km

Friday 23 February

The

alarm wakes us at 6.00am, at 6.25 weíre waiting for the restaurant to open and

weíre in the taxi by 7.15. Itís

a short ride but it costs us 18,000 pesos.

The

taxi ride when we arrived wasnít such a rip-off.

We check in and have time to send a few emails before we board.

We get glimpses of the

Taha Tai Hotel, Apina Nui, Casilla,

Location: 27.09S 109.27W (GMT -5

hours) 1,000 peso = £1

The airport is small, and the taxi ride to the hotel is only a few minutes (and

costs 1500 pesos). After the luxury

of the South American hotels the Taha Tai seems rather basic.

The receptionist is not very informative (or even communicative) and

mentions breakfast but not dinner. In

the room Sue sees a note that dinner must be booked before lunch.

Are we too late already? I

see a notice about island tours, and as we only have one full day (tomorrow) I

think we had better book it. I go

back to the receptionist. She

doesnít seem to want to take a reservation for dinner, but it seems that we

can eat in the hotel. I ask about

the tour round the island. She tells

me to go to reception in the morning. What

time? She looks as though no-one has

asked that question before. Around

9.30, 9.45. There are two tours

mentioned, a full day and a half day. I

ask for brochures or leaflets. There

arenít any. I say we want the full

day, but as no-on has booked a picnic she doesnít think it is running

tomorrow. OK, we will have the

half-day, whatever. I tell her I

canít get the safe to work, and she comes back to our room with me.

The safe is in a cupboard on the floor, and we both have to get down on

our hands and knees whilst she shows me how to operate it.

Then she leaves us to settle in.

We have a doze and then feel ready to explore.

We were handed a leaflet on dengue fever at the airport, which is quite

serious. There is no vaccine, and it

is up to us to make sure we donít get bitten by mosquitoes, so we cover our

exposed bits with insect repellent. We

step out of the hotel but we have no idea where we are in relation to the town

Hanga Roa although we remember reading that it was only a short walk from the

hotel. Or was that a different

hotel? We wander off in what

proves to be the wrong direction, but Sue looks back and thinks she recognises

the hanga (bay) of the town.

We go down to the sea and walk back, past the other side of the hotel.

We are soon adopted by an Alsation bitch.

When we approach more dogs they attempt to see off ďourĒ dog and she

takes refuge behind Sueís legs. We

stop at a restaurant for tea and cakes (how civilised) and our dog waits for us.

The restaurant proves to be on the edge of town, and we are soon looking

at our first moai (statue).

It is genuine, but we feel it has been put here for the tourists, and we

arenít moved by it. There is a

good selection of restaurants and we start to regret that we have committed

ourselves (if indeed we did) to eating at the hotel.

The dog stops every time we stop, and although we didnít want to touch

her eventually I reach down and pat her. Thus

satisfied (or repulsed) she loses interest in us.

The town has a frontier feel to it. Chickens

scratch around in the dirt, and people are riding horses, some of them bareback.

It must be more practical than importing a car, all its spares, and fuel,

from mainland-Chile, although there are some cars about.

We watch a large sea bird. We

both think ďfrigateĒ but we donít know for sure.

Back at the hotel we have dinner in a near-deserted dining room looking over the

ocean, with a cruise ship at anchor. We

can hear the waves crashing on the black basalt rocks.

Our waitress doesnít speak English, and even though the menu is

multi-lingual the corn soup we order turns into asparagus.

Sue has tuna pasta and I try for one of the anonymous fish dishes with

fried sweet potatoes. We both enjoy

it. What appears to be part of a

wedding party (or a stag party?) goes by, young people in pick-ups, but we hear

no sound of revelry. Back at the

room we have to come to terms with the toilet, which is the worst flusher in the

world. Not to put too fine a point

on it, I decide I need a stick to help matters along.

There are no sticks in the garden, so I borrow Sueís nail scissors to

cut a sturdy dead stalk from the shrubbery.

This is a far cry from the

Saturday 24 February

At 7.30am itís still dark. I

canít imagine how we can be so far out in the Pacific and only 5 hours behind

We collect more people (who all seem to be ready and waiting) at more hotels,

and then climb the hill to the south of the airport.

Our first stop is Orongo, a collection of ceremonial stone huts (some

reconstructed, most in ruins) where the young men went in Spring to prepare for

the physical and spiritual journey to become birdmen.

Elena, our guide, has only uttered the first few words when I recognise

the scene and, with a sudden jolt, I remember the ritual.

Instantly I am wondering about past lives, and then it comes back to me,

I read about this years ago, in a novel, I think.

Hmm, thatís a pity.

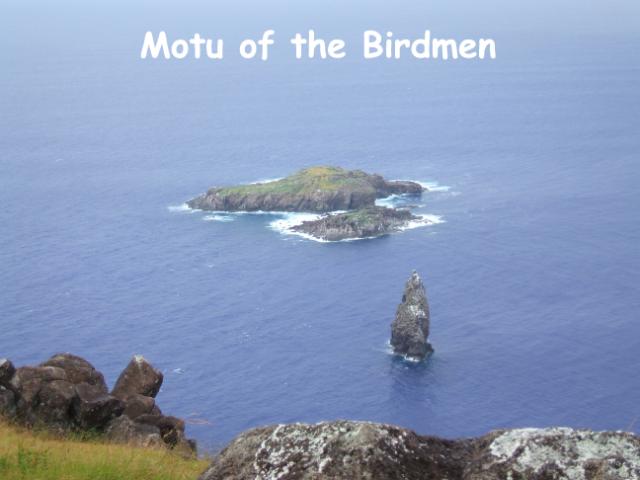

Off the headland are three small motu

(islands) used every year by nesting seabirds.

The young men must watch and wait, in their stone shelters, until the

first egg of the new season is laid. Then

the men must climb down the cliff, swim the channel, clamber on to the motu,

in a race to seize the egg. The

successful one swims back to Orango, bearing the egg in triumph, to become chief

for the next year. He carves a

petroglyph on a rock on the ridge between the sea and the volcano, making his

mark (half-man, half-bird) and signifying his birth (or rebirth) as a birdman.

It is an awesome prospect, but I can see merit in the system.

It would probably have prevented George W Bush and Tony Blair from taking

office. But oblivious of my

yet-to-be-formed opinion, the missionaries considered it a pagan ritual and put

an end to the birdman competition. Is

the world a better place as a result of the efforts of the Christian

missionaries? It is certainly a

duller one. I am still musing.

Of course, having read about the ritual doesnít automatically mean I

wasnít a birdman in a past life. I

cam almost feel the shock of the cold water, the exhilaration of the battle

against the strong currents and my rivals, the triumph of swimming back with the

precious egg in my mouth . . . Then

I probably sneezed.

Off the headland are three small motu

(islands) used every year by nesting seabirds.

The young men must watch and wait, in their stone shelters, until the

first egg of the new season is laid. Then

the men must climb down the cliff, swim the channel, clamber on to the motu,

in a race to seize the egg. The

successful one swims back to Orango, bearing the egg in triumph, to become chief

for the next year. He carves a

petroglyph on a rock on the ridge between the sea and the volcano, making his

mark (half-man, half-bird) and signifying his birth (or rebirth) as a birdman.

It is an awesome prospect, but I can see merit in the system.

It would probably have prevented George W Bush and Tony Blair from taking

office. But oblivious of my

yet-to-be-formed opinion, the missionaries considered it a pagan ritual and put

an end to the birdman competition. Is

the world a better place as a result of the efforts of the Christian

missionaries? It is certainly a

duller one. I am still musing.

Of course, having read about the ritual doesnít automatically mean I

wasnít a birdman in a past life. I

cam almost feel the shock of the cold water, the exhilaration of the battle

against the strong currents and my rivals, the triumph of swimming back with the

precious egg in my mouth . . . Then

I probably sneezed.

We walk past the huts which remind us of Skarra Brae, although the Orkney houses

are much older. We reach the lip of

the volcano and wait our turn to look at the carvings.

They have eroded badly with the wind and the rain, but there is something

primitive and timeless about them. In

front, the sheer drop to the sea and the bird islands.

Behind, the steep side of the crater of Rano Kau, 1,000m across, the

surface a long way below us mostly covered with water, 200m deep in the middle.

It is a wild place, there is rain in the wind, and it is 1,000 miles to

the nearest neighbour (Pitcairn) and 2,000 miles to the nearest population

centre. We are standing on the

remotest spot on earth.

The next stop is Ana Kai Tangata, where there is a cave with 15th century rock

paintings. The sea fills the cave

every day and the paintings have almost disappeared.

We take photos without much optimism.

On the way back we stop to look down on the airport, with Hanga Roa

beyond. There are distant views to

the north-east, across a green and pleasant island.

Coming back into town we ask to be dropped at the Post Office rather than

the hotel, and just make it before it closes.

We hand over our postcards and pay the extra $1 to have our passports

stamped with

We have lunch in a restaurant in town, with a view of the Hanga Roa moai

on the edge of the harbour. We only

want a snack, and once again we struggle with the menu.

We settle on a dish which has Coquilles san Jacques in the description.

It proves to be snack-size, small marinated scallops served with capers

and bread with mustard mayo and spicy diced onions.

We have slight misgivings when we realise that the scallops are uncooked.

I wonder uneasily if I will need my stick again tonight.

We buy chocolate on the way back to the hotel, and weíre ready for the

next tour in good time, as is Richard from

The first stop of the afternoon is the quarry at Puna Pau, the only place on the

island where the red rock used for the moai

topknots is found. There are several

topknots lying around in various stages of completion, abandoned when some

long-ago carvers downed tools. Some

are complete, at some short distance from the quarry.

They were abandoned on their journey to find the right head.

Then we are driven to Ahu Atio, also known as Ahu Akivi, where seven moai stand on their platform. (The

word ahu means platform.) They gaze

unblinkingly towards the point where the sun sets in the equinox.

We are thrilled: this is why we came to

Now we start heading west, and we are shown caves at Ana Te Pahu.

When the lava flowed and cooled several natural fissures were formed with

extensive tunnels and caves. The

islanders hid in these caves to avoid capture by the Peruvian slavers who came

looking for workers for their mines. It

wasnít an entirely successful tactic. The

population was decimated, not just by the departure of those captured but by the

diseases left by the Peruvians. The

caves do not look designed for comfort. Our

final stop of the afternoon is Ahu Vinapu, where there is a part-finished

platform that was being prepared for the biggest moai

of all. The huge blocks of rock fit

snugly together, and some experts think the skill involved shows a South

American influence. Elena thinks

otherwise. She is an islander

herself, and can trace her lineage back a long way.

She thinks the skills developed independently of each other, over 2,000

miles apart, and there appears to be no doubt that the people themselves are

Polynesian, not South American. There

is also a badly eroded standing stone depicting a female.

Elena tells us that the moai were created to commemorate clan chiefs, who were all men.

What position did this woman have, to warrant her likeness being carved

for posterity? We get back to the

minibus just before the heavens open, but the rain stops before we get back to

the hotel. I tell Elena that we

would like to go on the full day tour tomorrow, with picnic lunch.

Yes, she says, I have you booked for that.

I tell her I havenít paid for any of the trips, but she doesnít seem

concerned.

Unimpressed by my reaction to last nightís meal we decide to risk the weather

and walk into town for dinner. Before

we reach the town we see a restaurant with English words on the blackboard menu

outside. Itís not a wise choice,

for there is not much we fancy, but by now itís raining and we donít want to

walk even further from the hotel. We

settle for steak and chips, and whilst we wait they bring us some kind of

tortilla puffs rather than bread, and theyíre quite nice.

Whilst we are eating the steak the rain gets heavier and starts to blow

onto the tables at the front of the veranda.

The staff move the tables and chairs towards the back.

The steak is gristly, and Sue canít eat much of it.

Just off the veranda a dog sits in the pouring rain, waiting patiently

for scraps. It gets most of Sueís

steak. Still hungry, Sue decides she

will have a desert, but before we can order it we are forced back as well.

There are just two tables being used, and we all huddle against the wall

of the restaurant. We would go

inside, but there arenít any tables inside, just the kitchen.

We decide to forget desert and make a dash for it.

The waitress offers to get a taxi, which we decline.

Another mystery for

Sunday 25 February

It has rained all night and Sue is hoping that the tour will be cancelled.

It isnít, and off we go, after I have paid for the two days.

First stop is at Vaihu where we see fallen moai,

which is like seeing a neglected graveyard.

Except this isnít just neglect, the statues were pushed over

deliberately. They are so big (most

are between 12 feet and 20 feet high, and some weigh 80 or 90 tons) that the

toppling of hundreds, all over the island, must have taken a lot of time and

effort. It wasnít done in a

momentary fit of pique; somebody had to work very hard to push them all over.

These moai are by the sea, and

after the toppling further damage was caused by an earthquake in

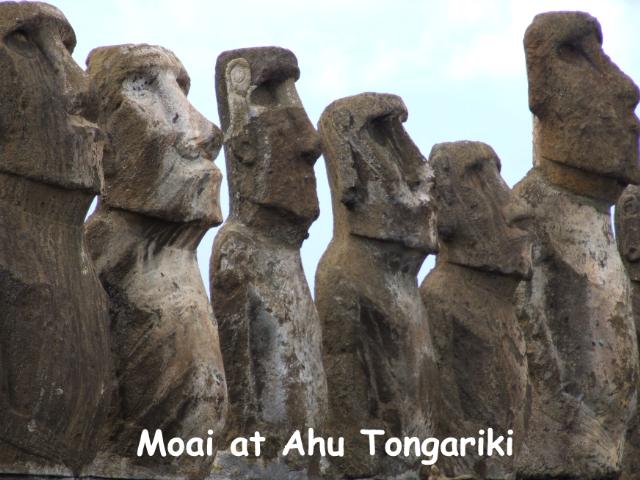

Next comes the highlight of the tour: Ahu Tongariki.

This ahu is enormous, over 20 metres long, with 15 re-erected moai. One has a topknot.

They stand in line, facing inland, with their backs to a wide bay.

In the distance we can see a huge quarry face, where the stone for all

the moai on the island was cut.

There is also a solitary moai, not on a platform, who had been borrowed by the Japanese.

On his return to the island, the Japanese showed their gratitude by

funding the reconstruction of the platform and the fifteen moai

whose broken bodies had been scattered by the tsunami in 1960.

This is an eerie and majestic place.

I have an emotional reaction similar to that when I saw the terra cotta

warriors at Xian, and I am moved almost to tears.

over 20 metres long, with 15 re-erected moai. One has a topknot.

They stand in line, facing inland, with their backs to a wide bay.

In the distance we can see a huge quarry face, where the stone for all

the moai on the island was cut.

There is also a solitary moai, not on a platform, who had been borrowed by the Japanese.

On his return to the island, the Japanese showed their gratitude by

funding the reconstruction of the platform and the fifteen moai

whose broken bodies had been scattered by the tsunami in 1960.

This is an eerie and majestic place.

I have an emotional reaction similar to that when I saw the terra cotta

warriors at Xian, and I am moved almost to tears.

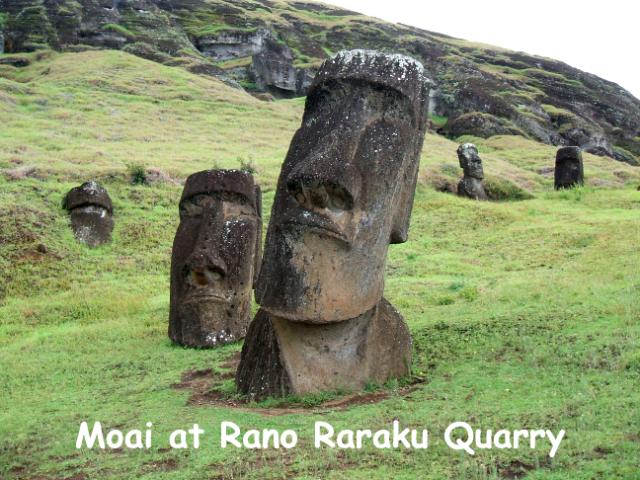

The minibus takes us near to the quarry at Rano Raraku.

We walk across the hillside, where statues have been abandoned as they

were being transported. Some are on

their backs, some standing, some partly buried, some at drunken angles.

At the quarry itself, we can see some that are unfinished, features

visible but still part of the bedrock. This

is work-in-progress. One of them was

destined to be the largest moai of

all, and we saw his platform yesterday at Ahu Vinapu.

The sheer scale of the operation is breathtaking.

There are almost 400 moai here.

The minibus takes us near to the quarry at Rano Raraku.

We walk across the hillside, where statues have been abandoned as they

were being transported. Some are on

their backs, some standing, some partly buried, some at drunken angles.

At the quarry itself, we can see some that are unfinished, features

visible but still part of the bedrock. This

is work-in-progress. One of them was

destined to be the largest moai of

all, and we saw his platform yesterday at Ahu Vinapu.

The sheer scale of the operation is breathtaking.

There are almost 400 moai here.

We wander back to the car park, which has tradersí stalls and picnic tables.

Our food has arrived in heated containers and we tuck into chicken, rice

and vegetables, followed by a banana. I

buy a shirt with a discreet image of a moai

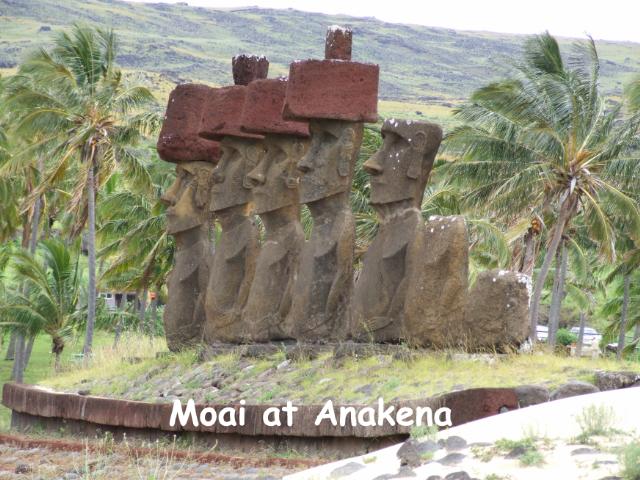

and Sue buys souvenirs, and then itís back on the bus to Ah Te Pito Kura, where Admiral Roggeveen saw the statues still standing in 1722, followed by the

beach at Anekena. Itís an idyllic

spot, with yellow sand, palm trees, and an ahu

with standing moai, several with

topknots. Itís a fitting end to

the day.

where Admiral Roggeveen saw the statues still standing in 1722, followed by the

beach at Anekena. Itís an idyllic

spot, with yellow sand, palm trees, and an ahu

with standing moai, several with

topknots. Itís a fitting end to

the day.

We get back to the hotel about 5.00 pm and having lost our room this morning we

have to rummage through our cases in the lobby, ask for towels, and shower and

change in the toilets. It has rained

on and off all day, although all the tour stops were between showers, but now we

are reluctant to go into town in case we get soaked again.

We eat at the hotel and I pay with the last of my Chilean pesos.

We have a few hours to wait for our ride to the airport, and we sit in

the lounge, reading, marking time. The

receptionist comes over with some news. Our

plane, the only plane of the day, has been delayed in

The plane takes off at 1.30 am, and we leave

Next

leg:

Next

leg:

Easter

Island to